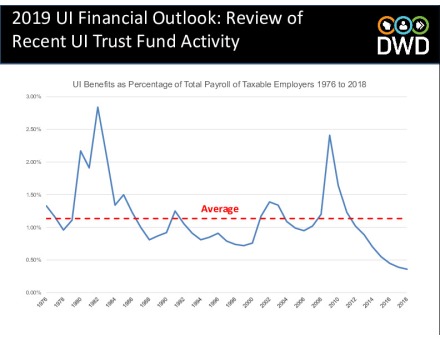

Mark Sommerhauser’s article about possible changes to criminal prosecution of unemployment fraud has a remarkable chart detailing the roller coaster plunge in unemployment benefits in Wisconsin since the end of the great recession.

In 2018, only $1.11 million in first-week unemployment benefits were paid out in Wisconsin. Here are some numbers to provide some perspective on this decline in unemployment benefits.

Historical comparisons

At the January 2019 Advisory Council meeting, the financial report included some jaw-dropping numbers regarding the stellar decline in unemployment taxes employers pay and the even steeper drop in unemployment benefits being paid to claimants. Tom McHugh explained during his presentation that benefit payments in 2018 had not been this low prior to 1994.

So, a comparison between the years 2018 and 1994 seems in order. Monthly claims history data reveal:

| Year | Init. claims | Benefits paid |

| 1994 | 430,452 | $405,625,564 |

| 2018 | 283,398 | $397,746,075 |

So, while the amounts of benefits paid are relatively close — a difference of around $8 million — there is a difference of 147,000 initial claims between the two years. These numbers mean that in 2018 the Department paid on average $1403 in unemployment benefits for each initial claim, whereas in 1994 the Department paid on average $942 in unemployment benefits for each initial claim that year.

In part, the lower number in 1994 exists because the maximum weekly benefit that year was only $243, whereas in 2018 the maximum possible weekly benefit rate was $370.

But, this data also includes information about the weeks being claimed versus the weeks that are actually compensated.

| Year | Weeks claimed | Weeks compens. | Prct. |

| 1994 | 2,589,895 | 2,443,988 | 94.4% |

| 2018 | 1,659,861 | 1,352,076 | 81.5% |

In 2018, just over 81% of the weeks being claimed were leading to actual payment of unemployment benefits, whereas in 1994 fully 94.4% of initial claims led to the payment of unemployment benefits.

The available weekly claims data for these years adds another eye-popping wrinkle to this comparison: the size of the labor force.

| Year | Init. claims | Covered emply. |

| 1994 | 452,526 | 2,301,412 |

| 2018 | 279,912 | 2,817,338 |

Note: changes in the number of initial claims being filed likely exist because of what is being measured: weekly versus monthly claims data.

So, in 2018 there was a drop of nearly 62% in initial claims from 1994 even through the number of covered employees actually increased by more than 500,000. If eligibility for unemployment benefits was the same in 2018 as it was in 1994, there should obviously have been more unemployment claims given the 500,000 employee increase in the eligible labor force. But, rather than an increase in claims in 2018 there has instead been sharp dive in unemployment claims.

Someone might argue that the workforce in Wisconsin has substantially changed from 1994 to 2018. That explanation does not hold much water.

This chart shows that there have been slight declines in manufacturing from 1994 to 2017 in Wisconsin as a percentage of the workforce (from 25.44% of the workforce to 21.21% of the workforce) as well as in public sector employment (15.06% to 12.84% of the workforce). But, the real changes have not been so much in the makeup of the workforce so much as in the percentage of who belongs to a union. Only private construction has NOT seen a dramatic drop in both union coverage and union membership from 1994 to 2017. And, those drops are by half or more from what existed in 1994. So, the decline in unionization is at least strongly correlated with the decline in Wisconsin employees receiving unemployment benefits in this state.

Fraud comparisons

The other major factor at play with the decline in unemployment benefits is the increased prosecution by the Department for alleging fraud.

As the Department’s fraud allegations are a relatively new phenomena (while unemployment fraud has always existed as a category, prosecutions did not begin in earnest until this last recession), this data cannot provide a look back all the to 1994. But, this data does reveal what the Department has been doing since 2011.

Here, the number of fraud cases as a percentage of total initial claims actually increased in 2013 and 2014, declined in 2015 and 2016, and has held steady at 1.67% of total initial claims in 2017 and 2018.

The over-payments being assessed as percentage of benefits being paid out, however, actually increased slightly in 2018, going from 1.11% of all unemployment benefits paid out in 2017 to 1.18% in 2018.

The decline in collections in 2018 from 2017 was more sizable, dropping from 3.14% of all benefits paid out to 2.58% of all unemployment benefits paid out in 2018.

Noticeably, the collection of over-payments allegedly connected to fraud were in 2018 still more numerous than collections for non-fraud over-payments. Only in 2011, the first year of the Walker administration, was the ratio of fraud to non-fraud over-payment collections well below 100% (at 55.51% that year).

What’s next?

This month, the Department announced that unemployment rates are at a record low of 2.8%. As Jake has described these numbers, this low unemployment rate masks significant job losses in Wisconsin. Wisconsin is trailing the rest of the mid-west in job growth (and the mid-west itself as a region is trailing the rest of the nation in job growth).

The 1994 numbers described above indicate that while the state’s economy has not actually changed all that much from what existed in 1994, the unemployment system itself has markedly change. Even with a maximum weekly benefit rate in 2018 that is $127 higher than what existed in 1994, total unemployment benefits being paid out are about the same in 2018 in absolute dollars (i.e., NOT adjusted for inflation), 24 years later. This stagnation is shocking.

The big change with unemployment during the last eight years or so is the expansive and aggressive charging of unemployment fraud by the Department for accidental claim-filing mistakes. The case law is now over-flowing with decisions about how the Department has charged claimants with fraud for accidental claim-filing mistakes, defended those charges despite all evidence to the contrary, and even sought retribution against those who dared challenge the Department’s wishes on this front.

And, it is obvious to anyone filing unemployment benefits today about how complicated and difficult the claims-filing process has become. It is now all too easy for someone to make an accidental mistake during their weekly claim certification and then find themselves facing charges for unemployment concealment simply for not understanding what is being asked.

Note: this confusion and resulting mistakes ares even more likely when language and technology barriers are considered. Unemployment claims are on-line only now and STILL only in available English.

Finally, the decline in union representation and coverage from 1994 to 2018 indicates that the institutions that could have raised alarms and fought back against these changes to the unemployment system today lack the strength and support to conduct such a fight. As a result, these fundamental and far-reaching changes to the unemployment system have occurred without significant challenges.